Приказ основних података о документу

Trade in the Central Balkans (11th-13th century): Between necessity and luxury

| dc.creator | Bikić, Vesna | |

| dc.date.accessioned | 2023-11-27T15:26:38Z | |

| dc.date.available | 2023-11-27T15:26:38Z | |

| dc.date.issued | 2016 | |

| dc.identifier.isbn | 978-86-519-2004-5 | |

| dc.identifier.isbn | 978-86-519-2005-2 | |

| dc.identifier.uri | http://rai.ai.ac.rs/handle/123456789/1107 | |

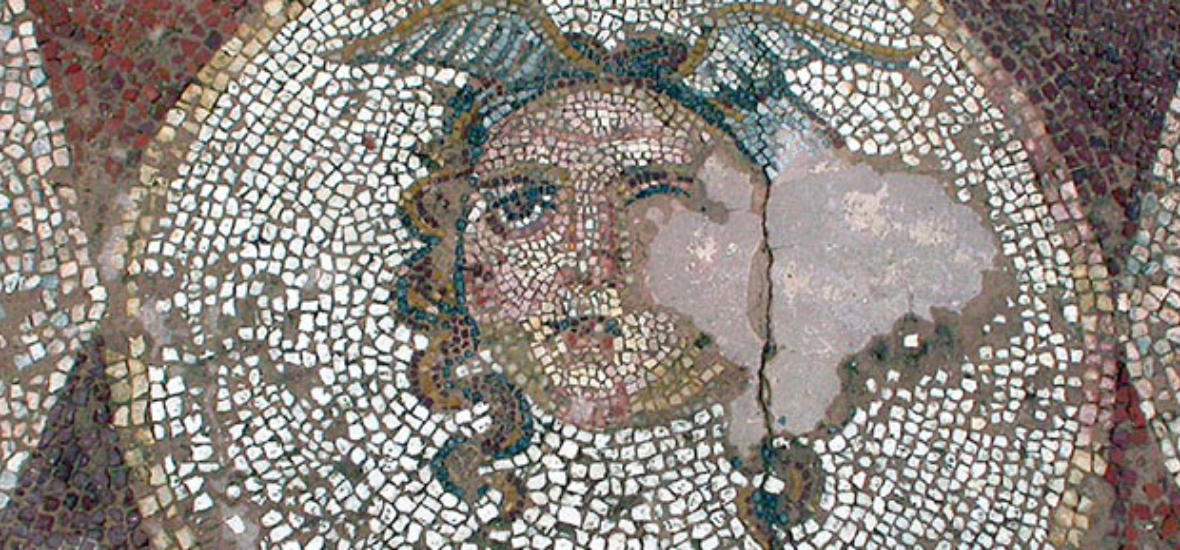

| dc.description.abstract | The active Byzantine policy in the Balkans, accompanied by the military operations during the 10th century, was completed in 1018, when the northern border of the Empire was re-established on the Danube.1 The military stations along the Danube and in the interior, next to the main waterways and roads, represented strongholds of authority, from where Byzantization spread into the surrounding areas. However, the battles within the reconquista campaign were not the last of the conflicts in the Balkans. During the next two centuries, Byzantium was forced to wage war several times, even on multiple fronts.2 Besides raids by the Pechenegs, Byzantium’s overall policy in the central Balkans in the period from the 11th to the start of the 13th century was defined, perhaps in the greatest measure, by conflicts with the Serbs and the Hungarians, their alliances and allies. In these cases, higher aims were the reason for the continual challenges to Byzantine authority – the permanent seizure of parts of territory, i.e. the creation of new states in the regions under Byzantine rule (fig. 64). Despite the uncertainties of wars on several fronts, this was a period of economic progress for Byzantium, expressed in a particular manner through exchange and trade.3 The more intense inflow of money, stemming from payments to the military, primarily noticeable in the Danube basin, and then along the road and river routes of the Timok, Morava and Nišava rivers, certainly precipitated an increase in the turnover of goods – not just of basic military necessities, but also of other objects, which can be categorised as luxurious.4 Thus, 1 Максимовић, Организација византијске власти, 31–34; Holmes, Basil II. 2 Stephenson, Byzantium’s Balkan Frontier; Madgearu, Byzantine Military Organization. 3 Laiou, Exchange and Trade, 736–746. 4 Радић, Иванишевић, Византијски новац, 27–38; Stephenson, Byzantium’s Balkan Frontier, 84–89. the consumption pattern became a significant indicator of the society, or of the economic and cultural level of a community. In addition to information from written documents, archaeological data can in this case also be viewed as an important indicator of past activities, which are relevant for the interpretation of phenomena in the economic and social dynamics of the given times | sr |

| dc.language.iso | en | sr |

| dc.publisher | Belgrade : The Serbian National Committee of Byzantine Studies | sr |

| dc.publisher | Belgrade : P.E. Službeni glasnik | sr |

| dc.publisher | Belgrade : Institute for Byzantine Studies, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts | sr |

| dc.relation | info:eu-repo/grantAgreement/MESTD/Basic Research (BR or ON)/177021/RS// | sr |

| dc.rights | openAccess | sr |

| dc.source | Processes of Byzantinization and Serbian archaeology. | sr |

| dc.subject | trade routes | sr |

| dc.subject | distribution pattern | sr |

| dc.subject | amphorae | sr |

| dc.subject | sgraffito pottery | sr |

| dc.subject | protomaiolica | sr |

| dc.subject | bronze vessel | sr |

| dc.subject | glass bracelets | sr |

| dc.subject | jewellery | sr |

| dc.subject | Byzantine strongholds | sr |

| dc.title | Trade in the Central Balkans (11th-13th century): Between necessity and luxury | sr |

| dc.type | bookPart | sr |

| dc.rights.license | ARR | sr |

| dc.citation.epage | 131 | |

| dc.citation.spage | 125 | |

| dc.description.other | Byzantine heritage and Serbian art I, ed. Vesna Bikić | sr |

| dc.identifier.fulltext | http://rai.ai.ac.rs/bitstream/id/2517/bitstream_2517.pdf | |

| dc.identifier.rcub | https://hdl.handle.net/21.15107/rcub_rai_1107 | |

| dc.type.version | publishedVersion | sr |